Friends, have you ever heard the story of the battleship and the speed-boat? If not, it’s a short but powerful fable. A battleship, a speed-boat, and several cargo ships were sailing through an icy sea. Only the battleship could afford to hit an iceberg, which was all well and good, as it was so ungainly that it could not steer round the bergs. Sadly, though the cargo ships were agile enough to avoid the bergs, doing so would put them right in the path of the battleship. The speed-boat had no such limitations, and effortlessly navigated through the ice as the cargo ships sank one by one, either from hitting an iceberg or getting hit by the battleship. As the voyage continued, the battleship began to encounter bergs so big that it could not simply run into them, but still it could not steer round them, so the captain ordered his gunners to blow them up. Chunks of ice flew all about, and sank the few remaining cargo ships, yet the speed-boat dodged them all. When at last only two ships were left, the battleship and the speed-boat, a huge wall of ice appeared on the horizon. The battleship continued on its course, guns blazing, only to ram the ice head-on and sink, leaving only the speed boat, which eventually found a crack in the ice wall and sailed straight through.

Unrealistic though this little tale may be, it is an important lesson about power. While the story I just told is my own (though not the first time I’ve told it), I didn’t invent the thematic analogy. Rather, it was one of my manufacturing engineering instructors who introduced me to it, but it’s applicable to more than just manufacturing.

The original analogy had to do with small business versus big business. I shouldn’t have to spell it out for you, but this being the internet, I of course, bloody will. The icy sea represents the market, the battleship represents big business and the speed-boat represents small business. In my version, the cargo ships are medium-to-large businesses, whereas the battleship is a “too big to fail” business. Just as the battleship was able to destroy everything in its path without ever changing course, “too big to fail” businesses are powerful enough to manipulate the market, and thus aren’t truly subject to market forces as small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs, not to be confused with the Society of Manufacturing Engineers) are. The speed-boat, naturally, is a small business with the capability to quickly change direction in response to both market forces and larger competition. With just a wee bit of adaptation, this fable could also apply to nations.

What is a nation? It is a people, the land they inhabit, and the culture that unites them. Despite the best efforts of the clergy sent forth from the ivory tower to shoehorn the word “state” into that definition, the nation and the State are not the same thing. A nation can exist without the State, but the State cannot exist without the nation. The State is a leech upon the nation, and if allowed to grow too large, it will eventually kill its host. Some of you reading this will already be in agreement with that exact sentiment, but this article isn’t for you; this article is for statists, those who believe that government is capable of solving every problem that a nation faces.

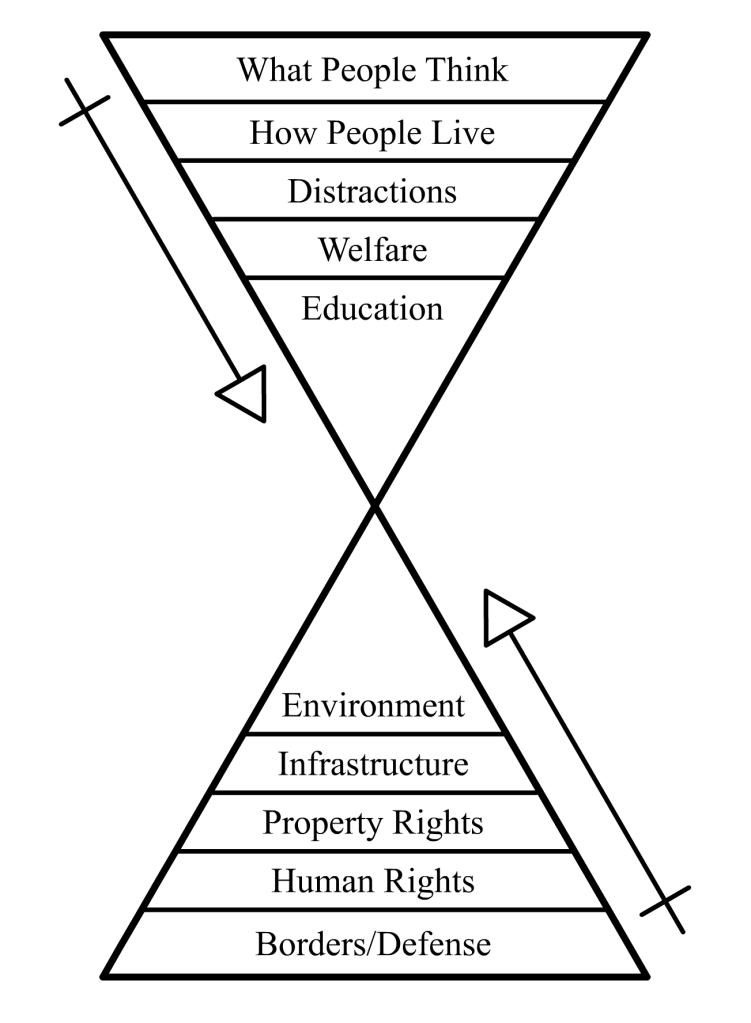

Government, regardless of its structure (republic, monarchy, etc.), comes in two basic forms: populist and progressive. Populist government is bottom-up (“of the people, by the people, for the people”) or decentralised, progressive government is top-down (“of the collective, by the learned, for the anointed”), or centralised. Daniel Tubb of the Lotus Eaters created a helpful illustration based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs called “Dan’s Hierarchy of Government,” and it looks like this:

You might have trouble reading this if you’re using Substack in night mode. Sorry about that, but my own background isn’t quite as dark, try reading it there. Anyway…

Long-time readers of mine (i.e. before I joined Substack) have already seen my breakdown of this idea, but I will go through it again with some improvements.

Borders/Defense – if you don’t enforce your borders, you don’t have a nation, simple as. Much as this may piss off the open borders sect of the dissident right (despite what you may have heard, such people do in fact exist), just as people have rules within their own house, nations have rules within their own territory. A wall isn’t necessary to keep people out unless your neighbours have a habit of coming in uninvited and, oh, I don’t know, creeping on you while you’re in the shower and then running off with one of your sheep (and that’s a tame example). This is the bare minimum of a “night watchman state,” a phrase which, I would remind you, was invented by Benito Mussolini as a criticism of liberalism before it was eventually adopted by libertarians.

Human Rights – Dan originally labelled this level as “life, liberty, happiness,” and said that he didn’t really like it that way. Therefore, I’ll call this level “human rights,” in the classical liberal sense. Jacob Tothe has written a rather concise article on this subject, so I suggest you check that out for elaboration. Self-preservation and self-determination are human rights; healthcare and housing are not, they are needs.

Property Rights – people steal from each other, and don’t always have the means to prevent or rectify that on their own. Should the government be able to protect its subjects’ lives from both outside forces and each other, the next step would be to protect their property as well.

Infrastructure – once a society has matured to the point where it is not merely a collection of private properties, it falls to the public sector to facilitate connections between private citizens, such as roads and utilities, in regions where the free market has not already provided such services; note that nationalisation of roads and utilities is not required in order to maintain public infrastructure, nor is eminent domain.

Environment – in some ways, environmental protections are actually an extension of both property rights and infrastructure, because littering and pollution can undermine the latter and directly infringe on the former.

Now we move to the inverted pyramid, which is top-down governance. These are the priorities, in order, of “progressives,” by which I actually mean authoritarians.

What People Think – propaganda is ubiquitous in authoritarian systems, and a handful of “examples” are regularly set via show trials in order to create the psychic illusion that the majority supports the system. Thus, most people who live under such a system and can see through the lies are left believing that they are the only sane person in a nation full of madmen.

How People Live – self-sufficient individuals are the greatest enemies of the authoritarians, because they demonstrate that the system is not a necessity. In order to make itself necessary, the State must make living without it impossible. The State therefore requires a monopoly on essential products such as food… sound familiar?

Welfare and Distractions – I combined these two simply because they are the modern versions of Bread and Circuses, respectively. The “Culture War” is certainly a type of distraction, but far more pernicious are foreign wars, which are generally a higher priority for authoritarian governments than social programs. Foreign wars also serve the additional purpose of keeping the government coffers full.

Education – authoritarian systems need a government monopoly on education in order to indoctrinate people into becoming true believers in the system, simultaneously determining where exactly they will fit in the system, all the while acting as unpaid government informants to rat out their dissident parents. In order to make people into perfect cogs, get them while they’re young!

Central planners, be they statist or corporate, rely on the methods of top-down government in order to achieve their ulterior objective, because in their minds, everyone must be of one mind. Whether it be a nation or a business, this is a terribly inefficient way to run things for quite a few reasons. By the way, if you’ve noticed a slight change in the writing style, it’s about to get even more obvious, because the warrior poet aspect of my persona is getting shoved in the proverbial cupboard while the equally sarcastic but infinitely nerdier engineer explains things in autistic detail. You have been warned!

Centralisation relies, somewhat ironically, on specialisation and compartmentalisation. In industry, this means each production unit (be it worker or machine) does precisely one thing. Should any production unit fall into non-operation, then everything downstream of it grinds to a halt. For this reason, each production unit should have some overlapping capacity in order to make up for inevitable gaps that will occur in the event a worker calls in sick or a machine is down for maintenance. This is one of the fundamental weaknesses of just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing; should you ever fall behind, you will never catch up again, unless of course there is a major lull in orders, and no sane business hopes for that. JIT is generally preferred by central planners because, at first glance, it appears to be the most efficient method, as it does not require large inventory spaces. In reality, JIT and lean manufacturing in general aren’t magic wands that can be waved about to solve every problem with efficiency, they simply trade one set of problems for another. In the words of Thomas Sowell, there are no solutions, only trade-offs.

Bearing all of these potential problems in mind, a well-managed factory will seek to do as much in-house as possible, so as to not be too reliant on an external supply chain. However, aside from the absolute largest factories in existence (e.g. Zavod № 183 in Chelyabinsk, Russia), no factory goes as far as processing its own raw material (and I’m not entirely sure if Zavod № 183 actually smelted its own steel back in the day, but it made large steel castings). However, industrial cities (Chelyabinsk included) are generally large enough to produce everything from start to finish. They will be located relatively close to supplies of ore, this way ores do not have to be transported particularly long distances to processing plants. From there, materials will move in one direction throughout the city, and the factories that produce finished products will be located closest to the main transportation hub, usually a port. Nothing just described requires central planning, rather it is the natural evolution of industrial cities. Speaking of evolution, this is where standardisation comes in.

Standardisation can be brought about by central planning, such as King Charles II of England ordering the standardisation of bricks in the immediate aftermath of the Great Fire of London in 1666, but in most cases, standardisation is the result of market forces, such as in the case of screw threads. How many different types of screw threads exist? Good question. There are: 55-degree Whitworth threads, 60-degree unified threads, 60-degree metric threads, 29-degree acme threads, 30-degree metric acme threads, square threads, 30-degree buttress threads, 45-degree buttress threads, ball threads, straight pipe threads, tapered pipe threads, cone threads, and the weirdest of them all, Hindley threads. That’s thirteen. There are thirteen different types of screw threads that I could name just off the top of my head. Each of these types can be further divided into other categories: coarse, fine, special (yes, that’s an actual classification), sharp, truncated (“stub” for acme threads, not applicable for square, buttress, or ball threads), right-hand, and left-hand. Seven different categories times thirteen types, minus the exceptions, is a whopping eighty-eight, and that’s before we get into individual size, pitch, number of leads (most have only one, whereas removable breech plugs on muzzle-loading rifles usually have three or four), and fit class (ordinary fasteners are class 2, precision machined threads are usually class 3). These are simply the standardised threads, some of them (e.g. 55-degree Whitworth) are obsolete, while others (e.g. Hindley) require such specialised equipment to make that they were never particularly common to begin with. Anyone who works with antiques (e.g. yours truly) must be prepared to deal with some truly bizarre thread sizes, because prior to standardisation and the subsequent mass production of taps, dies, and roll-forming equipment (how screws are mass-produced in fastener factories), screw threads would generally be made in the same manner as the components in these two videos. You don’t have to watch them to completion to get the gist of what is being done here (in fact, I originally intended to simply embed a couple of two-minute clips, but they took way too long to upload):

Though this thread can be identified (UN 1.125 x 12 RH), the fact that both components are made on a lathe specifically to fit each other means that they don’t have to adhere to any particular standard. Since this was the only way to make threads for centuries, screws weren’t particularly common, and the predominant way of fastening metal components was with rivets. What this means is that only the most commonly used screw threads ever had taps and dies made for them, and thus they became the standards. In fact, this is sort of where the name “unified” came from in the first place. Companies that stubbornly insisted on using their own proprietary threads didn’t do well in the market, because repairs of their products required customers to go all the way back to the original factory. Should the company go out of business, that left the customer needing a replacement for the product, unless of course they can find someone like me, and most either don’t have time or simply don’t care. Recall that I said Whitworth threads are obsolete? Well, I have seen them in the wild… on antique violin bows.

If all this talk about screw threads has you bored to tears, perhaps you understand just how complicated the job of a central planner would be, and thus why most of them aren’t very good at it. The larger the system, the more problems result from micromanagement. Over-regulation by government is nothing more than a form of micromanagement. The worst example of this is medicine, and not too far behind it is agriculture. The over-regulation of agriculture has favoured factory farms which, ironically, produce lower-quality food than the typical family farm. In order to offset the costs of adhering to government regulations (one of which is the requirement to employ a full-time inspector, yes, the farmer has to pay the goon’s salary), farmers have to find ways to make food as cheaply as possible. One such example is what Jacob Tothe refers to as “public meat.” Commercial livestock is bred to grow as quickly as possible, which results in less flavour and lower nutrient density than homestead-raised livestock or wild animals. Compare a homesteader’s chicken to a commercial chicken sometime, if you don’t believe me. Commercial chickens are ready for slaughter at six weeks old, and they don’t live much longer than that anyway. Depending on the breed, as many as 10% of them could drop dead before being ready for slaughter anyway, and that gets needlessly expensive in the case of anyone doing business with Tyson (I don’t know about other major chicken producers). All of this results in people over-eating and/or subsisting on vitamin supplements because they aren’t getting the necessary nutrition from their diet. If you want good food, you are stuck either growing it yourself or joining someone like me in a wee bit of black market activity (my farm would never pass inspection, even though my birds are a lot healthier than the ones you’ll see at any industrial chicken farm).

Centralisation has far more dire consequences than simply poor-quality food. The centralisation of government power frequently incites rebellions, which can result in nations being torn apart. You’ve heard the saying “national divorce is national suicide,” I assume. Well, national divorce is inevitable in the event of the national government assuming more and more direct control. This is currently a big problem in not only the United States, but Russia as well. For anyone with even a the slightest interest in Russia, you’ve probably seen your social media algorithms feeding you articles and videos about the Siberian secessionist movement, and this is no mere coincidence. Concerted efforts from the western hegemon to break up Russia aside (ask Victoria Nuland), Moscow’s focus on the 1% of the actual land mass where 90% of the population resides certainly makes things look good on paper, but the neglect of the rural areas, especially east of the Ural Mountains, has alienated large swathes of the Russian countryside. On the other side of the pond, Washington assuming more power over the affairs of individual states (for the worst, if that weren’t obvious) is, for the second time in the country’s history, inciting secessionist movements. This will lead to another civil war if the federal government doesn’t back off, and I suspect that this is by design, given what came immediately after.

Now then, what can be done about the problems of centralisation? Well, despite the temptation to keep a low profile and not tell anyone what you’re up to, that’s actually a terrible idea. While I have seen plenty of libertarians (you know who you are) advocate for a return of the guild system, that would result in a degree of technological regression virtually identical to Warhammer 40,000. How? Easy: without some kind of publically-available blueprint, every machine becomes a black box that must be taken apart to be understood. If the machine is held together with screws, this means that every screw must be measured to see what profile it has. Is it metric or imperial? If imperial, which empire? French inches aren’t the same as British inches (Napoleon Bonaparte, for example, was 5 feet 2 in French inches; in British inches he was 5 feet 7). On electronic devices, it gets even more complicated. If a computer uses a proprietary operating system, then only the company that made it would be able to produce software for it. A free market, of course, would eventually select against the products of more secretive companies in favour of anything open-source. Of course, there may still be a demand for proprietary whatever if the product is good enough, but that won’t stop an enterprising autist like me from reverse-engineering it. Leonard E Read was wrong; even if no-one currently knows how to make a pencil, someone could figure it out. Besides, there are already a million-and-one ways to make a pencil, just saying.

Anyway, I’ve prattled on long enough. The whole point of this is that you should strive to be as self-sufficient as possible, but don’t feel pressured to do everything yourself. Seek out others to help you develop your skillset, and also those who can do things you can’t.