On the Fourth Industrial Revolution

It's inevitable, but it's not what the WEF is trying to push

This is going to be a little history lesson on the structure of industrial revolutions, and why the self-appointed architect of the fourth one is just plain wrong about almost everything.

There have been three industrial revolutions thus far, and they have all been brought about by the proliferation of certain inventions. The first was brought about by the steam engine, the second by the electric motor (no, seriously, I will explain), and the third by the personal computer.

For most of history, powerful machines reliant on rotary motion could be built only where there was enough flowing water to drive a massive wheel. The only other option was to use ridiculous amounts of manpower.1 Then along came the steam engine… circa 100 BC. However, it never went anywhere, and is remembered only by nerds like me who actually listened to those history lessons in engineering school instead of dozing off like everyone else who is just there to make stuff. Anyway, the simple reason that the Hero Engine, which is a type that was eventually re-invented (it’s called a reaction turbine) is because the Roman Empire had slaves, and therefore there was very little motivation to build complex mechanical force multipliers. There were a couple of other steam engines built in later centuries, but it wasn’t until 1720 that they started to proliferate. This was after European countries began to abolish feudalism and chattel slavery. Not all had done so, but what happened next shows the advantages of an industrial society over a slave or feudal society: massive economic growth. Slavery was a barrier holding society back, and the handful of places that still practise it have the same problems today that slave societies did 300 years ago.

Steam engines never went away, they are still important in industry, they simply aren’t as prominent, and that is because of two other sources of rotary motion that are far more common. Vehicles of all types replaced steam engines with internal combustion engines, and factories replaced steam engines with electric motors. Most people, when asked what brought about the second industrial revolution, will say “Henry Ford’s assembly line,” but I’m going to change your mind on this slightly. First of all, Henry Ford didn’t invent the assembly line, he got the idea from observing a meat-packing plant, and thought that he could run the same type of operation in reverse in order to quickly and efficiently assemble vehicles. However, Ford was simply taking several previously-developed industrial methods and combining them into a single, self-contained manufacturing plant. Besides the assembly line, the most important part of the modern manufacturing plant is the ability to produce interchangeable parts. Interchangeable parts are another remarkably old idea, apparently even used by the Ancient Carthaginians, which would explain why they could build ships as rapidly as the Romans could raise armies. However, it wasn’t until 1765 that the idea started to proliferate, and this was because of the firearms industry. The idea of producing identical components that did not require tremendous amounts of extra labour to fit together, was developed independently in France and the American colonies. Eli Whitney gave a demonstration of his capability to produce standardised muskets from interchangeable parts in 1797. However, this practise really only worked in isolated batches unless a “master template” was kept around to be carefully measured and duplicated; in fact, I once worked in a shop that did precisely that on account of most of the workers being unable to read blueprints. However, with Sir Joseph Whitworth’s major contributions to the development of precision measuring instruments and machine tools in the 19th century, the production of interchangeable parts was made far easier. Whitworth also developed the first standardised screw threads, though his system is no longer in use and not likely to be encountered by anyone who doesn’t work with antiques.

Factories with precision machine tools necessary to make interchangeable parts were tremendously expensive to set up, and that’s because the factories themselves were giant machines back in the 18th and 19th centuries. There were no small machine shops like mine, and the reason came down to power. Every factory had a massive steam engine to power line shafts, also known as overhead belt drives. Line shafts actually pre-date steam engines…

…so what the steam engine did was allow such workshops to be built basically anywhere, instead of being bound to waterways. All machines in the factory were run off this system, so the single steam engine had to be powerful enough to run every machine in the factory. Naturally, this also meant that, when the steam engine wasn’t running, nothing in the factory was running. This posed a problem. Anyway, since the broadest truths are best illustrated by painstaking specifics, I’m going to use one of my own machines as an example of just why the electric motor is so bloody important.

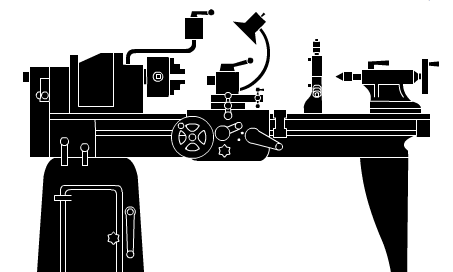

My lathe is something of a “transitional form,” in that it is an early example of an electric machine tool, but you can still see how it was developed from an old line shaft machine tool. I have seen much older South Bend lathes that don’t have a motor and pulley underneath the headstock, in fact the man I bought my milling machine from had one, and added a motor and drive pulley to it. The point I’m getting at is that, without the electric motor, a lathe is useless outside of a massive factory with overhead belt drives. I would not be able to have precision machine tools - a necessity for certain types of work that I do - in my tiny shop in the middle of bumfuck nowhere were it not for the electric motor.2 Forget electric lights, rural electrification enabled more sophisticated machine repair and even light industry in rural areas, facilitating some much-needed decentralisation. Good luck farming with a tractor if your only way to repair it is to have it towed all the way to the city, whereas your local machine shop - my machine shop if you live anywhere near me - will be sufficiently equipped to make any replacement parts you might need. Anyway, on to the next industrial revolution!

In the mid-20th century, Thomas Watson, the president of IBM, claimed that there was a global market for about five computers.3 That take aged like milk, didn’t it? There doesn’t seem to be any debate that the proliferation of the personal computer (PC), followed by the widespread installation of the internet in 1994, facilitated the third industrial revolution, otherwise known as the beginning of the information age. However, there is so much more than mere information that the PC facilitated, such as Personal Computer Numerical Control (PCNC) technology, a subset of which is 3D printing. This technology allows people to produce almost anything they need in the comfort of their own home, and the availability of information allows them to teach themselves some fairly complex skills. In fact, I have already made some contributions to this in the form of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) tutorials and a walkthrough of backyard investment casting, and I plan to do more when I have time. Point being that no longer is it necessary to congregate in a centralised facility to learn anything; all of it can be done remotely, there is no longer a tradeoff of technology versus rural living. Completely gone are the days of people needing to congregate in massive smog-choked heat-islands we call “cities,” or at least they would be, if not for a certain group of envious, scheming cultists driven by their eternally seething hatred of the productive class.

Whether it be cars, household appliances, or electronic devices, the companies that produce these things are becoming less open about how they work, and as a result, the average consumer is more reliant on “black box” technology than 20 years ago. People don’t repair their own cars anymore because they can’t, modern cars are damn near impossible to work on. PCs can be tinkered with, but not smartphones. A purely mechanical device can be taken apart to see what’s broken when it’s not working properly, but good luck doing that with a device that performs the same functions electronically. This is where we get into the obvious deception of “The Great Reset”: it’s not a reset of anything,4 but the logical conclusion of a trend that western civilisation has been on for a few decades now. To quote myself from The Great Reset is Anything But, written back in 2021:

Corporations have been undermining the concept of personal property for the entire 21st century, so far. Software companies are the worst, as they have, in almost perfect lockstep, moved away from allowing consumers to “own” copies of their software, and instead switched to subscription services, in which the software is perpetually rented. This is a shady (more like “shitty”) business practise that allows companies to continually siphon money from their customers on a single product, rather than having to regularly introduce new products in order to get repeat customers (though they still do that, too). Since it is such a successful business practise, companies that produce tangible products are looking to do the exact same thing, and some already do.

Bad business practises such as this are not successful because of market demand; nobody wants this, but the oligopolies have no meaningful competition. Companies that were once great examples of innovation have become self-parodies of what they started out as, all because they have been infiltrated by adherents of an ideology that explicitly rejects creativity, though they will happily re-introduce the same thing with some tiny changes in new packages as “the next great thing” every other month, a major contributing factor to our modern “throwaway society.” Nobody who has thought about this for more than five minutes wants this. There will, eventually, be a fourth industrial revolution, but Klaus Schwab won’t be able to take the credit for it, because he has nothing to offer. He is on the right track in his speculation that the invention that will bring it about may already exist (some people think it’s cryptocurrency, he’s stuck in the past thinking that it’s brain chips), but no-one can say for certain if this is the case. Furthermore, none of the previous three revolutions were brought about by central planning, which is all that the WEF is offering; the organisation isn’t inspiring technological innovation, it is simply suggesting insidious uses of technology that already exists in support of a nearly 200-year-old ideology that has a consistent track record of failure. The previous industrial revolutions were all about “doing more,” but the WEF is promoting “degrowth.” Look, even if you buy the narrative that the Earth is over-populated, the mass extermination of large swathes of the population is not the way to solve the problem; people who are more affluent tend to have fewer children, and even in the “third world,” quality of life is increasing and birth rates are dropping. The population will eventually stabilise without meddling from central planners. History has shown that the Professional Managerial Class (PMC) is basically useless, hence their desire to drag the productive class down to their level; anyone who isn’t one of them and is of no value to their agenda is a “useless eater,” a hylic, a democratic unit whose only purpose is to be part of a mass that legitimises their power until… well, let’s not get too mystical right now, I’ll save that for a later article.

So, what about my predictions? Well, truth be told, I have no idea how this current paradigm ends, but based on the ideals of Hans-Hermann Hoppe combined with a decentralised cryptocurrency-based market or neo-barter system,5 here’s my apocaloptimistic take: after the collapse of the neo-liberal world order and the idea of post-national authority is dealt a final blow, the people who are hopelessly dependent on the current system will either stay in their crumbling hive cities (unless

is right and the “retake the cities” crowd outnumbers the “let it rot” crowd) to be ultimately forgotten, but in the outside world, the socio-political as well as geographic periphery,6 a new type of society will rise in this Dark Age of Technology, and no, I don’t say this just because I’m a 40k nerd, I say this because, in some ways, it will resemble the Dark Ages.The term “dark ages” has fallen out of fashion, but I still like it to refer to the period immediately after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, otherwise known as the “early middle ages.” Anyway, during this time, the European landmass was dotted with tiny settlements inside extremely primitive wooden ring forts. Each of these “holdfasts,” for lack of a better term, was an entirely self-sufficient miniature town; it housed farmers, millers, weavers, tanners, and a blacksmith or two. Some skills were, more or less, universal, such as cooking and carpentry. The collapse of the neo-liberal world order, or “society as we know it” will certainly not send us back to the Dark Ages technologically, but what comes afterward will end up resembling it on an organisational level; there will, for a time, be insufficient resources to facilitate mass transportation of necessities such as food. Therefore, a rapid transition to local production will be required, and in some areas, namely rural areas inhabited entirely by people who were red-pilled long ago, this is already happening. The main difference is that technology has given rise to specialisation that was once unnecessary, while simultaneously, paradoxically, allowing people to develop much more generalised skillsets. For example, in the actual Dark Ages, there weren’t many ways to work with metal: there were fondeurs, who smelted metal, the smiths who worked metal, and that was it. Later on, there would be more specialised metalworkers such as platers (so-named because they made plates that armourers would then work further), but it took a long time before any other techniques would be developed. Machines have made it possible for one person to do everything. That being said, trying to do everything entirely on one’s own is extremely draining, ask me how I know. Therefore, the Technological Dark Age community will end up being a collection of homesteads in which different people aim to be as self-sufficient as possible, but will still end up specialising out of necessity; even farmers specialise in different crops, because some of us have a greener thumb for certain plants. Expect to see a significant overlap of skills, but cooperative efforts will result in the greatest productivity. How long before the rapid innovation of the early 20th century is replicated, resulting in a technological Renaissance? I have no idea, but that will be the real “fourth industrial revolution.”

Anyway, that’s all for now, I have a treehouse to build, and assuming I don’t drop a floor joist on my head trying to raise it in place, I’ll be back next week to talk about the dichotomy of individualism and collectivism, and more specifically, to address a few common misconceptions about these positions.

Before anyone chimes in with “muh windmills,” I’d remind you that windmills traditionally never did anything more than grinding grain or pumping well water, hardly the sorts of high-power applications that water wheels were traditionally used for.

Before anyone chimes in with “but Sasha, there have always been small steam engines that were capable of being run off of a home heating boiler,” yes, I know, I built one! However, they were never particularly common, and of all the weird machines I’ve seen over the years, a steam-powered lathe was not among them.

There is a lot of conflicting information about this quote; for example, some sources claim that this quote was originally made in 1943, others in 1958. Furthermore, no source specifies if it was Thomas Watson Sr, first president of IBM, or Thomas Watson Jr, second president of IBM.

Plato believed in five forms of government, and that they were cyclical: aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny, in that order. The “reset” is so-named because it is a completion of a neo-Platonic penta-cycle of society:

Five modes of production are known to history: primitive communal, slave, feudalist, capitalist, and socialist. – Iosif Stalin, On Dialectical and Historical Materialism

Communism is defined as the abolition of private property, and “stakeholder capitalism” is simply “state capitalism,” the working definition of socialism in The Communist Manifesto. Ergo, the WEF is a Communist organisation, its members believe that humans evolved to be communists, and that they are completing the cycle to get us “back” to communism.

Look into “time stores” some time, which were somewhat common on the American frontier during the 19th century. The basic idea is that people with no money could trade their time working in the store in order to purchase the goods in that store. They didn’t last for very long, but a derivative could potentially be made to work with some technological enhancements.

It would be logical to assume that politics would become liberal, while all of its marginalized opponents surviving in the peripheral fringes of global society would reconsider their strategies and formulate a new united front according to Alain de Benoist’s periphery against the centre. But, instead, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, everything followed a different script. - Aleksandr Dugin, The Fourth Political Theory

I liked and agree with your views. Yes, there's a strong tendency of totalitarianism, but you only show concerns on the WEF side of the coin. I also made it, I made a whole "prophesy" about it. If you wish to read it it's on my substack, maybe you already have read it. (It really isn't a prophesy, it's just a extrapolation on speculations of the future based in current tendencies, the 'technique' of exaggeration that members of Frankfurt School and Günther Anders used).

Whereas the WEF side wants a kind of liberal-socialist coup, we also have what seems to be the liberal-capitalist side. The Silicon Valley pigs, Musks, Thiels, Altmans... and they are making their alignments round' the world, namely and notably Milei & Bukele (even Israel!). It's nasty. "Order and progress", at what cost though?

What you have to say? Is it a false dichotomy in the end, by the way? Are they all in this together? Or are the 'elites' actually divided between those paradigms?

I've been reading your stuff too, you are always dunking on marxists, the mainstream ones are shit, I have a motherlode recommendation of decent marxists.

Love the mill. Some of the old machines, motor/belt driven, are the most reliable ever built and easiest to repair. I'm not a metal worker, I've only dabbled, but it's fun and I've been at auctions where I've been shocked at what those old machines can go for.

You're right on the homesteading front, though. In my little community, everyone that moves here tries to do everything. And looks down on people that can't do some things. It's nuts and silly. We're all human, and have strengths and weaknesses. We all contribute what we can, and come together as we can.